The research project Relocating Modernism: Global Metropolises, Modern Art and Exile (METROMOD) marks out a unique and unconventional map of life and work in exile metropolises in the first half of the 20th century. It refers to urban topographies, inner-city districts, outlying suburbs and streets, to places where interactions took place, but also to the venues used for exhibitions and collaborative projects. Urban locations were of particular importance not only for communicating, forming networks and formulating theories; they were also stations on the diverse paths of exile.

METROMOD focuses on six metropolitan destinations for refugee European artists between 1900 and 1950, when wars and dictatorships, violence and oppression forced thousands of artists to emigrate. New York, Buenos Aires, London, Istanbul, Bombay (now Mumbai) and Shanghai were important arrival cities or transit points for artists in the fields of modern visual arts and architecture. The selection of these cities reflects the geographical and cultural extent of the exile movements of European artists and their local urban impacts. It takes into account various political systems – from the Turkish Republic to cities shaped by colonialism, like Bombay and Shanghai. The six cities also represent various climatic zones, topographies, traditions, languages and artistic preferences. As a key problem the project challenges the concept of Modernism as fixed, stable and western.

It aims to overcome established and still dominant narratives of Western European Modernism with its centers in Paris, Vienna or Berlin. METROMOD will contribute to a paradigm shift in writing modernist art history as a history of global interconnections, spurred by migratory movements and with an emphasis on instability, flux, contacts and networks.

The methods of the project combine urban study with art history and exile studies: the aim is to build a conceptual triangle of migration, modernism and metropolis to investigate how modern art changed in interrelation with local metropolitan cultures and artists.

METROMOD pursues three key objectives: Firstly, it explores transformations in urban topographies and institutions like academies and museums; secondly it focuses on actors and their artistic networks, artworks and exhibitions as crucial contact zones; and thirdly it examines media as discursive platforms between locals and migrants. The project follows interconnections between the cities as well as a comparative approach. The results of the five-year project (2017—2022) will be communicated by digital mapping, locating the settlement of artists, studios, institutions and exhibitions on urban matrixes.

METROMOD follows the hypothesis that the migration movements of artists in the first half of the twentieth century had a profound and long-term impact on art, architecture and photography history by establishing new transnational places of artistic encounter in global metropolises where concepts and works were significantly changed.

NEW YORK: FRANKFURT-ON-THE-HUDSON

Did you know, that the famous Blue Note Label, synonymous with jazz and other Afro-American music forms, was (ironically) founded by two German emigrants in New York in 1939? Or that Washington Heights in Manhattan was also known as Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson? During the 1930s and WWII, New York became home to many European artists, intellectuals, musicians and photographers fleeing National Socialist persecution. While the city offered the emigrants new career opportunities, they, in return, played an important role in increasing its allure by providing a rich diversity and cosmopolitan flavor.

Situated on the harbor, New York was a popular destination for the exilic ship passage from Europe to America. After days at sea, the skyline and the Statue of Liberty was seen by many refugees as a symbol of hope and freedom. German-Jewish emigrants often settled in the quarter of Washington Heights, in the northern part of Manhattan, or the borough of Yorkville (Lower East Side), where they built new communities and social infrastructure. Newly established restaurants and bakeries, such as the Café Vienna, served as important cultural places and meeting points for the European exiled literary and artistic circles, including the network around the writer Oskar Maria Graf.

Important professional hubs were established in collaboration and exchange with local residents especially in Midtown and Downtown, where they opened new galleries, magazines, newspapers or photo agencies. This is the case for the journal Der Aufbau and the photo agency Black Star, which were directly situated at the heart of the publishing and photo industries – around Madison and Lexington Avenues in central Manhattan. Both Der Aufbau and Black Star provided important professional platforms and networks for emigrated European journalists, writers and photographers during the 1930s and 1940s.

Crucial to the success or failure of the emigrant artists were patrons and gallerists as well as networks and institutions. In 1942 Pierre Matisse hosted a show titled “Artists in Exile” in his gallery featuring Ossip Zadkine, Max Ernst, and André Breton. Also, Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of this Century, which opened in the same year, became an important site for exiled surrealist artists. The New School, which employed emigrants such as German theorists and philosophers, surrealist artists and photographers, was also a key location for artistic and intellectual networking where the emigrants could give lectures, take part in workshops and also had the opportunity to experiment with new techniques. For the artistic and intellectual scene of Europe, New York was the cultural capital and center of American exile.

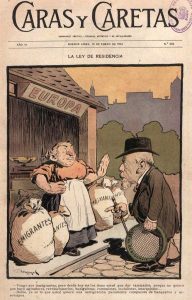

BUENOS AIRES, A COSMOPOLITAN HUB

In 1911 the Hotel of Immigrants was built in Buenos Aires to provide first accommodation to the thousands of people coming from Europe. With an average of 160,000 entries per year in the first quarter of the 20th century, Buenos Aires had a highly cosmopolitan population which made new arrivals feel at home. Within this context, the artistic and cultural scene was extremely rich and varied, allowing multiple magazines, galleries and exhibitions to cover the needs of hundreds of artists working in the city.

In the first half of the 20th century, Buenos Aires was a major urban center where hundreds of foreign artists settled, looking for a better economic and socio-political environment, or fleeing the interwar famine or Nazi persecution. Indeed, migration waves had been so significant since the 1870s that strong networks of European communities attracted hundreds of artists and intellectuals to choose Buenos Aires as a land of exile. Responding to this cosmopolitanism, journals were published in a range of languages: Argentinisches Tageblatt, The Buenos Aires Herald, Le Courrier de la Plata, La Patria degli Italiani.

Migrant artists received support from communitarian institutions – including the Casal de Catalunya, the Centro Gallego, the Circolo italiano, the Casa de Rusia, the Deutscher Klub, and the Israelite Congregation – which carried out cultural and political activities and helped them to integrate into the local artistic scene. Besides that, local networks were widely open to migrants. Within the cultural milieu, the Association of Friends of Art (1924) developed activities in different fields. The Association of Artists, Journalists and Writers (1936) brought together local and exiled artists and intellectuals committed to contemporary aesthetics and current political issues. Its magazine Unit for the Defense of Culture contains illustrations of artists including the Spanish engravers Pompeyo Audivert and the German Clement Moreau.

The magazine Sur (1931) founded by Victoria Ocampo was to become a major place of encounter in Buenos Aires for nearly two decades. The Jewish-German photographer Grete Stern, the Spanish painter, engraver and designer Luis Seoane, the Czechoslovakian sculptor Gyula Kosice were among the dozens of artists and intellectuals who were part of the magazine’s circle. Gallerists and art dealers with migrant backgrounds – Federico Müller, José Artal, Alejandro Witcomb – also supported these artists by inviting them to exhibit. This rich socio-cultural and institutional context welcomed and fostered the integration of European immigrants in Buenos Aires which was a hub for artists and intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century.

LONDON EXILE

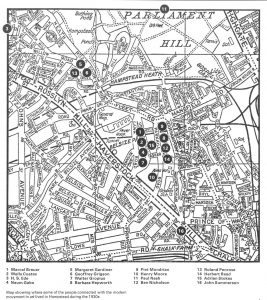

In the 1930s and 1940s, London became an important target city for modern artists fleeing Nazi-Germany and the occupied countries. Many emigré artists settled in Hampstead with its vivid modern art scene. At the same time, when the Hitler regime banned modern art from museums and galleries, it was shown in several exhibitions in London. The interaction between local and foreign artists, collectors and art critics lead to productive times in the metropolis on the Thames. Nevertheless, difficult working conditions for artists and architects and the growing threat of war drove many exiled artists to other destinations.

In the United Kingdom, immigration procedures in the first years after 1933 were so restrictive that initially only a few exiles arrived, among them notable artists and scientists. After 1938, the British government introduced a new visa system and relaxed admission requirements. From the November pogroms of 1938 until September 1939, about 40,000 emigrants, including many Jewish refugees, were able to enter the UK. London was the destination for many emigré artists. One of the main self-organized institutions was The Freie Deutsche Kulturbund (Free German League of Culture) with an anti-Nazi agenda, providing its members with visibility and a public platform through exhibitions, concerts and lectures. The Free German League’s clubhouse was located in Hampstead. Mapping the community of foreign and local artists and architects in this quarter it is obvious that they lived and worked close to each other: Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Naum Gabo and Ernö Goldfinger shared the same neighbourhood, and not far away Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer lived in the Lawn Road Flats.

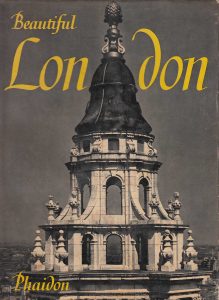

These shared urban areas could be called hubs of architecture and art production and theory. Manifestos like Circle, a book published in collaboration between Gabo, Nicholson, Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy in 1937 could have been prepared in the studios and apartments located in Hampstead. This leads to questions like: How were cities and their artistic topographies changed by the presence of exiled artists? How did the exile experience and the city shape the work of the emigrés, as it is visible in Beautiful London, a photobook (1950) by Helmut Gernsheim? Which neighbourhoods besides Hampstead became home to large numbers of migrants and how did they support contact but also segregation, exchange and isolation?

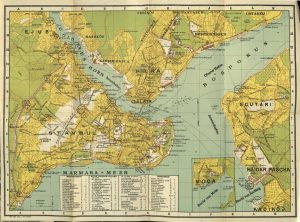

ARRIVAL CITY ISTANBUL

As a city on two continents with a multi-religious and multi-ethnic population, Istanbul offered emigrants heterogeneous experiences of arrival. Depending on the neighborhoods, their development and population, the proximity (or distance) to the water, or the accessibility by public transport, Istanbul showed different faces. Its topography gives numerous clues to explore the interaction of migration or exile, architecture and city.

Istanbul has a long history of the internal and transnational migration. As the centre of the Ottoman Empire and after the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the city became a destination for people who had to change their place of residence for economic or political reasons. The metropolis on the Bosporus was an important destination for refugee artists in the first half of the 20th century. Districts such as Beyoğlu/Galata were the target of various emigration movements, under them the Russian emigrants arriving after the Russian Revolution and shaping a “Russian Constantinople”. By “Russian”, of course, Jews, Armenians, Tatars and many other Russian-speaking people running for their lives were also implied. Among them were prominent representatives of the art community: writers, artists, musicians, choreographers. Some of them came to Istanbul for a while in order to move to Europe one day, others understood that they might stay forever. Something similar happened to painters whose short stay in Istanbul can be considered as a fact of great cultural significance. They depicted historical events, urban and rural landscapes, scenes from the Ottoman life. In addition, they painted still lifes, portraits and nudes. Their activities attracted attention of art collectors and dealers from different countries, many paintings of the so-called “White Russian” masters were sold. However, the work of the masters was not limited to paitings. Thus, Nikolai Peroff completed wall paintings for churches of the Russian settlements in Karaköy. Nikolai Kalmykoff was a magnificent muralist who painted wall panels and ceilings of cinemas and domestic buildings. His most famous work still adorns the Süreyya Opera House in Kadıköy.

At the end of the 1920s and during the 1930s, German-speaking architects, urbanists and artists worked and lived in Beyoğlu/Galata. Although the quarter was not far away from the historical centre (Stambul), it had also been shaped along European lines with embassies, bookstores and schools. Institutions including the Academy of Fine Arts or the Architecture Technical University were within walking distance, as was the port of Karaköy with its ferry boats, connecting the European and the Asian sides of the city. At the port of Karaköy the exiled architects Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Wilhelm Schütte created a temporary street architecture to celebrate the 15th anniversary of the Turkish Republic in 1938.

Several buildings designed by refugees, including private homes, university buildings and schools, are still standing today. Sculptures by Rudolf Belling, and projects and buildings by Bruno Taut can be read as testimonies of a practice in exile. Special means of expression are undoubtedly residential buildings, which were built in Istanbul in connection with its topography, such as Ernst Egli’s Villa Ragip Devres in Bebek (1932/33), the Villa Eckert-Emirgan by Clemens Holzmeister in Rumelihisari (1943/44) or, above all, Bruno Taut’s house in Ortaköy (1938) with a panoramic view of the Bosporus. Architecture and Art journals such as Mimar (later Arkitekt) or Ar, based in Istanbul, were forums for contact between migrant and local authors.

BOMBAY MIX

Along with Shanghai and Singapore, Bombay (now Mumbai) was one of the major Asian port cities to allow entry to Jewish refugees until the late 1930s. Although the entry requirements were tough and the total number of migrants did not exceed 5000, the small group of exiled artists in Bombay had a lasting impact on the city’s emerging artscape.

Following 150 years of Portuguese control, the British East India Company began developing the small settlement of Bombay into a centre of trade in the mid-17th century. Founded on a site unsuited to urban expansion, Bombay’s seven islands were connected through the construction of causeways and embankments, with further land being reclaimed from the sea. The 19th century opium and cotton trades brought the city’s first economic boom, making Bombay an Asian port city that rivalled Calcutta (now Kolkata), Singapore, Shanghai and Batavia (now Jakarta), and the most important city in India in economic terms.

The flourishing economy also triggered a process of rural-urban migration, and by 1900 Bombay’s population numbered almost 1,000,000. Famed for its cosmopolitanism, Bombay is a city of migrants. Among the rich mix of communities, two stand out as key contributors to Bombay’s civic infrastructure: the Parsis and the Baghdadi Jews. Pioneering industrialists belonging to the indigenous elite invested their fortunes in landmark projects such as the Taj Mahal Hotel, or the Sassoon Library. They were also crucial players in the development of Bombay’s artscape, investing in art education (J.J. School of Art), art societies, cinemas, theatres, and galleries, while also building art collections. Through their patronage and commitment to the emerging contemporary art realm, these figures and institutions also supported exiled artists from Europe.

Refugee artists who gained entry to Bombay included the Polish painter and illustrator Stefan Norblin, the Hungarian photographer Ferenc Brenko, and the Russian painter Magda Nachman Acharya. However, it was a trio of Austrian emigrants who exerted the most sustained impact on Bombay’s cultural scene: Walter Langhammer, painter and art director at the Times of India, Rudy von Leyden, art critic for the Times of India, and Emmanuel Schlesinger, an entrepreneur and art collector. They catalysed the emergence and popular reception of the Progressive Artists’ Group, which included now-canonised Indian artists such as F.N. Souza and M.F. Husain, and taught, criticised and collected art. Together with the local art community and figures from the local cultural elite, such as Homi Bhabha and Kekoo Ghandy, the exiled artists brought art to Bombay’s formal and informal spaces in the form of gallery exhibitions and salons – at Mulk Raj Anand’s home at 25 Cuffe Parade, for example – enriching the cultural life of the city.

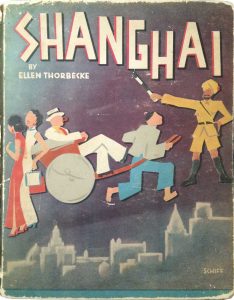

SHANGHAI (上海) – A CITY UPON THE SEA

By tracing venues of artistic practice, networks and contact zones, Shanghai can be highlighted as a creative hub marked by transcultural practice and continuous urban transformations constitutive of the global phenomenon of modernity.

As a treaty port following the Treaty of Nanking (1843) Shanghai’s exceptional territorial realities facilitated the entry of thousands of refugees, among them over 18,000 European Jewish refugees – the majority arriving in Shanghai between 1939-41. Sailing from Italy with stops in Port Said, Colombo, Singapore, Manila before finally landing at the banks of the Huangpu River, refugees were directly dropped in the heart of the pulsing metropolis north of the Bund. With the outbreak of WWII a new land route led refugees to Shanghai via Siberia and Manchuria on the Trans Siberian Railway.

In 1939 with the newly built market hall in Hongkou at Chusan Road, the opening of a new school and the revitalization of the business scene by the new arrivals, Hongkou partly became the heart of the European exile community and was known as Little Vienna. Largely destroyed and abandoned by the Chinese population during the first year of the Second Sino-Japanese war (1937-45) the influx of European refugees added a new layer to the urban fabric of Shanghai. Other centers were located around Bubbling Well Road in the International Settlement or Avenue de Joffre in the French Concession whereas the Old Chinese City remained closed to foreign experience, underlining the colonialist topography of the multiethnic metropolis.

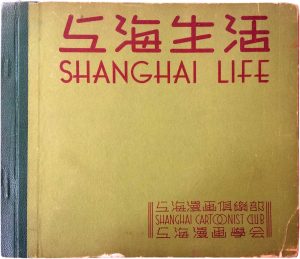

Local everyday life and ‘exotic’ street scenes offered an attractive motif and fruitful source of imagination for foreign, emigrated and exiled artists including David Ludwig Bloch, Friedrich Schiff or John Hans Less who exhibited, among others, in associations such as the Association of Jewish Artist and Fine Art Lovers, the Shanghai Cartoonist Club or the Shanghai Camera Club. Apart from public spaces such informal spaces as artists’ studios, bookstores, cafés or even nightclubs became exhibition venues and meeting points. The rich media landscape and advertisement industry offered jobs for capable illustrators, photographers and writers to guarantee a basic income.

Newspapers and magazines founded by émigrés, such as the Gelbe Post (1939-40) published by Josef Storfer, the former director of the Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag in Vienna, evidence a rich urban life of diverse social and cultural events. Exhibitions, theater plays and concerts complemented lectures and seminars covering topics like The Early Chinese Surrealismheld by the exiled art historian Lothar Brieger-Wasservogel.

In 1943 Japanese military authorities forced all Jews who had arrived after 1937 to move into a ‘designated area’ – a run-down part of northern Hongkou. With the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 the vast majority of stateless Jewish refugees left Shanghai.